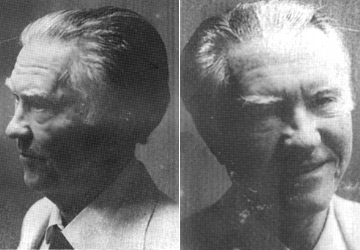

I interviewed the poet William Stafford when I was the Managing Editor of the Elgin Community College Observer (ECCO). This appeared in the November 3, 1989, issue.

William Stafford: poet, objector and activist

Mike Ortlieb, Managing Editor

William Stafford, originally from Kansas, has experienced a history that has included being a pacifist during World War II, a peace activist during the 1960’s, and working at the headquarters of the Church of the Brethren. He has a Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Kansas and has taught English at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Oregon. Since his term as a conscientious objector, he has found himself “drawn to writing meandering sequences of thoughts, or patterns of words.” Some of his books include: Down in My Heart, An Oregon Message, Writing the Australian Crawl and the recently published A Scripture of Leaves. Stafford appeared at ECC on October 11 and 12, conducting workshops and a poetry reading/lecture. He is the winner of the National Book Award for Poetry, and is a Consultant of Poetry at the Library of Congress.

The following was an interview conducted with Stafford prior to his evening poetry workshop:

The following was an interview conducted with Stafford prior to his evening poetry workshop:

You’ve not only been a poet, but your history includes that of a conscientious objector and peace activist. Tell me about that.

Around the last year of World War II, I worked here in the Office of the Brethren Services Division. And we were right down here… at the Brethren Headquarters… and we had a staff of maybe 10 or 12 people, and I was, for a while, the Assistant Education Secretary for Brethren Services and then the Education Secretary to last. But I was drafted out of college at the beginning of World War II, just a few days after Pearl Harbor, and I was sent to conscientious objector camps. First I started in Arkansas, then in two or three places in California, and then back here working for the Brethren. So, ever since then, I’ve been a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the War Resistors League, Vietnam Protests…

I imagine the Sixties were a thrilling decade for you.

Well, the Sixties were exciting for many people. Of course, I was well into my teaching career by then. And in a way, I felt I was given too much honor by the students of the Sixties. They said, “Oh! You were an objector! It was pretty hard to be one!” And I thought, “Yeah. It was hard to be one, and it was also a little bit more tough to decide whether to be one, because that was the ‘Good War’ so-called… the popular war,” so I didn’t know I deserved all their attention! And still, I did feel at home. I traveled to campuses all over… Kent State, Berkeley, Stanford — all those places where they had protests–and I was part of that… those years.

“These silent moments tenderize the writer getting ready for our harpoons.”

Stafford, at workshop before poetry critiques

What do you feel when you write?

I feel exhilaration about the adventures that come to me in the language. It’s not like writing something that I had intended to write. It’s more like finding out what will happen if I begin to write about any old thing that comes along. Writing anything – poetry or stories or essays or letters – is like letting something happen between you and the language. You write down something, you suggest something else: in the syllables… the chances of language are always varying at something else. So I like to adventure forward when I’m writing and let the process itself bring about things to say. And the satisfactions are not in… well, it’s not to be paid if you are paid, but…poets are miserably paid… the rewards are in the adventures in writing.

In your workshop, you mentioned some of the works of e.e. cummings. What poets have made an impression on you?

Well, I’m going to confess to you that I have met this question before, and sometime ago, it suddenly occurred to me that people are asking, “What other person most influenced your writing?” And the person who most influenced my writing – the person whose voice I hear in what I write – is my mother! And she was not a great writer, but she was an enthusiastic talker. And it suddenly occurred to me that no matter what people say when they’re asked this question, if you press them and say, “Who REALLY made the most impression on you?” Most likely your mother or father would be someone nearer to you than T.S. Eliot or Thomas Hardy or someone like that. These voices that are part of your life when you’re young, sustained part of your life, who have been with you while you were undergoing experiences that made you what you are – those I think are the voices that really influence you. I do read a lot, but it seems to me that our adventure in language – all of us – comes only partly from reading, and much more from talking: with friends, listening, talking, writing, reading. I do write a lot, and I read a lot, but I think the real river of language is in the talk that’s all around us.

“I quote you in the Senate.”

Eugene McCarthy, on Stafford’s work

In your own writing, what have you (or what have other people) thought is your strongest work?

The poem of mine that gets around the most is one called “Traveling Through the Dark.” It gets into anthologies – all kinds of anthologies – but I wrote it quite a long time ago, and I’m sick and tired of it myself, to tell the truth. But they use it for discussions, and I think it is a good discussion poem. But the thing that I have written that has earned me the most money is an article called “A Way of Writing.” It’s in my book, “Writing the Australian Crawl,” and it just gets into all sorts of books on writing, and the little magazine [in which] I first published it keeps sending me checks! They get permission from publishers and they’ve got enthusiastic …I get these notes from them. One of the editors that keeps writing me: “Again! We strike again! Keep it up, Bill!” There’s something that gets around even more. It’s become folklore. In fact, it was printed in Sports Illustrated. It comes from some coach, and then they got a lot of letters protesting [it]. The coach was a plagiarist. It’s a little letter that’s supposed to be from the head of an English department, written to a football coach and the letter says something like this:

Dear Coach,

We’ve often talked about cooperation between athletics and the academic part of our school. I approve of that, but I have a proposal that you cooperate with us. I have a student in English, and he has a good chance to become a Rhodes scholar. In order to make it, he should have a record in athletics, and we are hoping you will put him in the backfield [or whatever it’s called] so that he may show the committee from Oxford that he has had experience in athletics. And we promise you that he will bounce the football [or whatever one does with a football… it shows a lot of ignorance the way a coach would have about English] but, of course, he won’t be able to come to practice very often because he’ll be so busy with his studies. Let me assure you [he is sincere] that he will come when he can.

Well, this letter I see up on college bulletin boards and so on… [it] shows you it’s a way of getting back… professors to get back… which is usually the other way around. That’s gotten around more than anything else. It’s still mine, but it’s now folklore. I don’t know what I like the best myself. Something recent… well, I would say maybe one called “Storytime.” It’s not yet out, but it’s coming out. Maybe I’ll put it in my reading.

When do you expect your next book out?

Well, it’s in the works, but I bet it won’t be out for a year…it takes a while.

What do you find about today’s writers that you like or dislike?

I lean towards liking current writers, for what was evident – right there in our workshop this afternoon – kind of this readiness to write out of their own lives. And, when I was in school, I think things were much more formal. We thought that, in order to write, you study form and whatever’s current today, and you try to homogenize your own self into this whatever [mode] it is now and get yourself published. I think now there’s more venturesome… adventure in it. There’s a kind of readiness to plunge into the experience of telling things and with your own voice and not to worry about what the editors are accepting this year. In some workshops, they try to gear everything toward… aim towards a certain magazine, study your audience, and so on… I like better the idea of letting the audience figure it out for themselves… go ahead…write from the center of your own life, as I think more people are doing that now.

“There is America’s greatest living poet.”

Gwendolyn Brooks

With the recent controversy with the Art Institute [“Dread” Scott Tyler exhibit in March, 1989], do you find that society might be tending to become more conservative?

Yes, I’ve thought about this a lot. I suppose all people who are in writing and the other arts have thought about it. In fact, I even wrote to our Congressman about it, but I want to try to be balanced and put before you a point of view. I feel that there are many things being written now and many works of art that I don’t have much interest in. And I don’t like them, and I don’t tend to go to shows. So, there’s that, and here’s where it gets bad. They have in some towns… they say: “We’re going to meet, and we’re going to read aloud all the banned books!” Well, I believe in the freedom of banned books, but there are a lot of banned books I don’t have any interest in… so it’s a great burden to me to go hear all of ten books read, and I don’t tend to like them just because they’re banned… you see what I’m getting at? So I don’t think that Jesse Helms’ dislike beatifies a book. I’m not that kind of liberal. In fact, for all I know, some of his tastes would be my tastes. But his taste in what to do about it is not my taste. But I believe in the freedom to have what people want to do in the arts, and I’d believe in the freedom of staying away if you don’t like it.

Is there any advice you might have for today’s college student?

College is getting awfully expensive sometimes. If I were headed for college today, I think I’d be looking around for alternatives. If you think about it – how many thousand you have to put in each year, and what you could do with that – I’m thinking about this, for instance: when Tomas Mann and his brother were college age, their family set them up with enough money to live in Italy for a year. It was wonderful. I think they never forgot it. And think of what you could do with say, $15,000… So, remember, I would say to college students, you’re buying something–or your parents are. Are you getting your money’s worth? That’s one thing I would say. The other thing I would say in choosing a college: unless I had a certain course in mind that was taught only in certain places, in which case, I would borrow or do whatever it took to get there if I had to have it. And, if it weren’t for something like that, I would counsel people to go someplace where it’s near, congenial, and inexpensive. I don’t think that’s orthodox advice, but it’s possible to put out more than $15,000 a year to go to some college of your choice, and find after you get there that you’re not in touch with the people you intended to be in touch with when you do get there. There’s no guarantee they’ll be there. The best of them may not have time for teaching. So their names may be in the catalog, and they may even be in the schedule, but there’s some question about whether they’ll be in the class. I mean, there are all of these things to watch out for, and there’s some colleges in places where I just wouldn’t want to live, so I’d like to choose a place where I’d like to live, doesn’t cost too much, and convenience. I think there’s a lot of inflation in first-ranked colleges.

On Indian Hill: at ECC

1. Morning

Three flags in front salute the wind. A couple,

their legs in step, go scissoring by, the girl

possessed by the arm of her man, her body responsive

as his guitar; his eyes, a hippie’s — wide,

gray — have seen too far,

searching for some new Manitou.2. Noon

The slow, lean car of the cop prowls by,

and a newspaper cartwheels through the parking lot

forlornly in search of an open spot where the oaks

and pines once owned this land when the Indians

listened for Manitou.3. Evening

Older now, the wind comes back, retracing

its path, folding the flags. Late students, lost

in their underground, play the computer room,

faces reflecting what all screens tell:

“Calculation is the death of Manitou.”4. Midnight

Fingering grass, a little breeze flows,

reclaiming this land, scouting at night for the years

that will bring the return of Great Manitou.– William Stafford

Do you think there are enough dreamers in the world?

Actually, maybe it’s my fate, but I have a hunch that there are a lot of dreamers, really. Even Jesse Helms has interesting dreams. Of course he won’t tell you what they are. But in a way, I translate your question to me: “Do you think people are too cautious?” I think people are too cautious about their own lives. I mean, about the time they spend in things. They tend to invest their time in activities designed to help them succeed – whatever that is – and, as an “art major,” I feel they’re missing life, and the vividness of experience is so precious that you give up a lot if you throttle your interests in order to follow where the market goes or what the trend is. I think artists – real artists – know this, so that to most of society, they seem divinely reckless, artists do. And they are actually exercising the true conservatism – the saving of loose parts of your life that are really alive and precious.